On your blocs: Eurovision is coming!

Hugh dives past the sequins and the songs of Eurovision and looks at what the data says about voting blocs.

What’s the most important vote on May 18? Sure, there’s the one that’s compulsory for most Australians and will determine the course of the country for the next three years, but there is another key vote going on thousands of kilometres away in Tel Aviv, Israel… Yes, Eurovision will again be happening, now in its venerable 64th year.

There’s a lot to love about Eurovision, even if the music isn’t your cup of tea. The show itself is undoubtedly a spectacle, and with it comes a large dose of goodwill and positive internationalism. It is also the one time of the year Australia can pretend to be part of Europe.

But does the best act always win? Or do countries vote for those they naturally align with politically? UK commentator Terry Wogan famously quit as a commentator amid comments around bloc voting. It has been an issue historically, but as a Wikipedia editor tactfully notes, ‘it is debatable whether this is due to political alliances or a tendency for culturally-close countries to have similar musical taste’. Let’s have a look at the data to look for the presence of voting blocs.

Datagraver has helpfully put together a database of Eurovision voting data for 1975-2017 on Kaggle, making it easy to have a look. We have:

- Considered jury voting only (sorry, live audience)

- Considered only grand final voting

- Only report on countries that competed in the 2017 competition (and not attempted to map former states to current ones) – 42 in all. This means I accidently left Russia off the list, as they boycotted that year.

In the final, a country can give points to any other (but not itself), with 10 nonzero scores to dole out (12, 10, 8, 7, 6…1). For each year we calculate the vote country A gives country B minus the average number of points country B received in that year. We can then average this measure over all available years to get an average ‘bias’ for how country A votes for B.

This is a pretty crude but reasonable measure of bias – if country A always favours B then this measure will be positive, and a negative score indicates a tendency to not allocate points when others do. The crudeness comes because we ignore the number of times a country has the opportunity to vote for another, and also any trends over time.

On this basis the biggest love-in is the intuitively appealing Serbia voting for Montenegro: even though it only has had one opportunity to vote for Montenegro in a final, Serbia gave them the maximum 12 score, for this performance that few others favoured. The biggest grudge also involves Montenegro but appears to be against Australia – they’ve only given us 4 votes over 3 years, which is well below average.

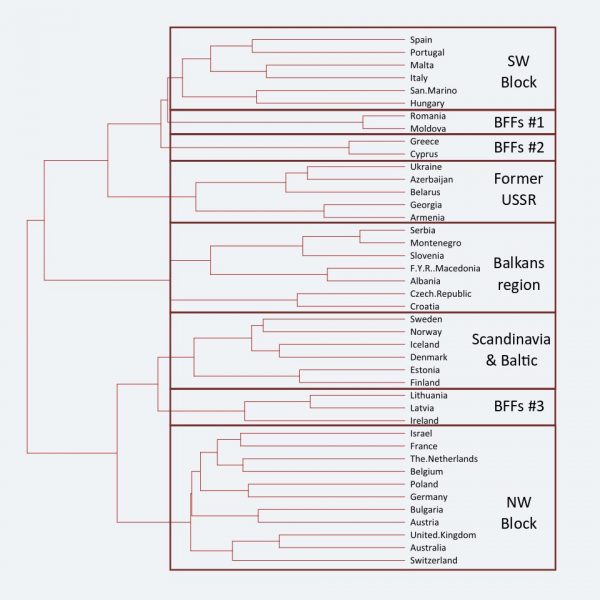

We can make the scores symmetric (take the average measure for AàB and BàA to get a joint relationship strength between A and B), and stick this into a hierarchical clustering algorithm to get a more comprehensive look at blocs. The results are shown, in a rough and ready form, in the dendrogram below. If you’ve not read one before, the main thing is that countries linked together further down the tree are ‘closest’ together in terms of reciprocating votes.

So who is our best friend? The UK, who must think they’ve finally found a buddy, followed by perennial neutral Switzerland.

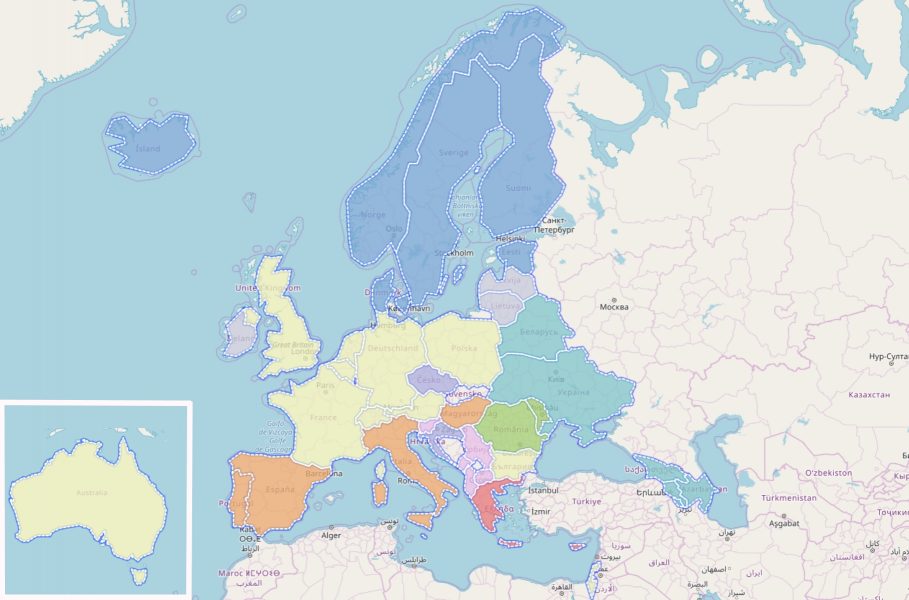

The strongest duos appear to be Greece and Cyprus, plus Moldova and Romania, who consistently reciprocate with votes. In terms of the eight groups shown, the geographical grouping is uncanny, given we only provided the algorithm with historical voting patterns. There is a northwest bloc, a southwest bloc, several eastern European blocs, a Scandinavian bloc and then former Yugoslavia nations forming groups of countries that tend to favour each other with votes. These blocs are shown on the colour-coded map below.

And tips for 2019? The betting markets are pretty good guides. As at the time of writing, the Netherlands is the favourite, for Duncan Laurance’s crooning. Australia’s Kate Miller-Heidke is well behind in the odds, behind other acts such as the Icelandic techno-punk band Hatari.

But, as ever with Eurovision, you never quite know what you’re going to get.

Technical notes

- The hierarchical clustering used the hclust function in R, with Ward clustering calculation. The dissimilarity score was 12 minus the average of A→B and B→A bias scores.

- Want a proper analysis of the data that considers things like trends over time? Try this article here.

As first published by Actuaries Digital, 9 April 2019

Other articles by

Hugh Miller

Other articles by Hugh Miller

More articles

Well, that generative AI thing got real pretty quickly

Six months ago, the world seemed to stop and take notice of generative AI. Hugh Miller sorts through the hype and fears to find clarity.

Read Article

Inequality Green Paper

calls for government policy reform to tackle economic equality gap

In a Green Paper commissioned by Actuaries Institute, Hugh Miller and Laura Dixie, analyse the impact of economic inequality in Australia.

Read Article

Related articles

Related articles

More articles

Accuracy and causality the hot topics in data science at SIGKDD 2022

Tom Moulder shares his top picks from the lively discussions at the recent knowledge discovery and data mining conference in Washington DC

Read Article

Lessons learned one year on – Algorithm charter for Aotearoa New Zealand

Take a look at the lessons learned from Taylor Fry's newly released review of the Algorithm charter for Aotearoa New Zealand

Read Article