The surprising life of Taylor Fry co-founder and actuarial guru Greg Taylor

Entrepreneur, pioneer, academic, musician – Greg Taylor has lived many lives in his 58 years as an actuary and built a towering reputation along the way. Not bad for someone who happened upon the profession looking for an easy life. Elizabeth Finch spoke with the Taylor Fry co-founder and discovered a truly quiet achiever, driven by a desire to do the right thing and an insatiable curiosity for the new.

You are considered a guru by many in your profession, even by your fellow Taylor Fry co-founder Martin Fry, who said he always felt like a junior partner. How does that make you feel?

A little uncomfortable. ‘Guru’ is flattering, but unwarranted – I would never recognise it in those terms. With age comes a certain deference, perhaps. I’ve just been around a long time!

It’s a surprise coming from Martin because I always thought of him as an equal when we were working together, and he’s a lot better at some things than I am. It’s difficult to believe he felt like the junior partner – he may be exaggerating.

Greg Taylor in our Sydney office

The Actuaries Institute has awarded you the only gold medal in its 121-year history and speaks of you as a pioneer in your field. How do you explain being the only one?

I’ve asked myself the same question. In the past, it was unusual to work across industry and academia, which proved a big advantage for me, but it’s an accident I chose that course and others didn’t – a case of right place, right time.

There’s always a tendency to accord a person superlatives, not only in this but in many aspects of life, to start ranking people. But I don’t see it in terms of rankings – everyone is good at something.

What do the awards, accolades and international acclaim mean to you?

Acceptance and recognition of my peers – that’s important to me – although my interest in research isn’t changed by awards or lack of them. Research is supposed to be useful, so awards also recognise someone thinks your research is useful and the people you mingle with in a research community regard the work as valuable. I can’t ask more than that.

Despite all the achievements, you remain quite unaffected. Was creating a relaxed culture important in setting up your own business?

Yes, it was very deliberate at Taylor Fry to have an environment that allowed people to be themselves. Many of the firm’s qualities reflect our early-day reactions against aspects of our previous work lives we thought were unfortunate – or not even quite proper.

There are some workplaces where rewards come to the noisiest, those who intimidate others and promote themselves. We didn’t think this was healthy and did what we could to prevent it.

Given that you’re held in such high esteem, have you ever felt pressure to be a role model?

No, I’ve always just tried to be myself. I actually never aspired to start a consulting firm. That path wasn’t a natural fit for me. I’d never contemplated it or thought it was something I’d be good at. It fractures your life and brings with it the risk of failure.

Alan [Greenfield, the youngest of the three Taylor Fry co-founders] was the galvanizing force for me. He was the one who said, “Look, we can do this.” It was only then I began to take the prospect seriously. I also took the risk very seriously. Martin did as well. Alan was a bit more gung-ho.

We were all refugees in a sense, driven by what we saw as the enormous shortcomings of our then employers. It was so bad and we doubted moving elsewhere would improve the situation.

Did the risk weigh heavily on you at the time?

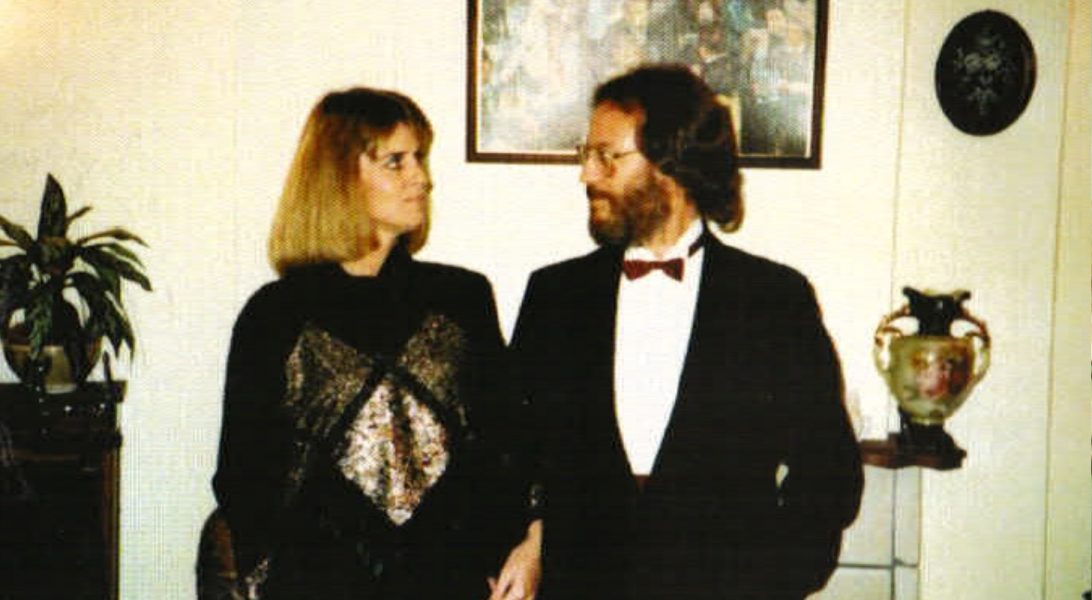

Risk is something you ignore at your peril, even if you rate the risk as low, which I didn’t. It’s wise to be constantly aware of it, to never overlook it. Not that it was ever likely to be forgotten. Martin and I had just mortgaged our houses and our wives regularly reminded us of this. That said, over the years, my wife Rhonda provided a great deal more support than was my due.

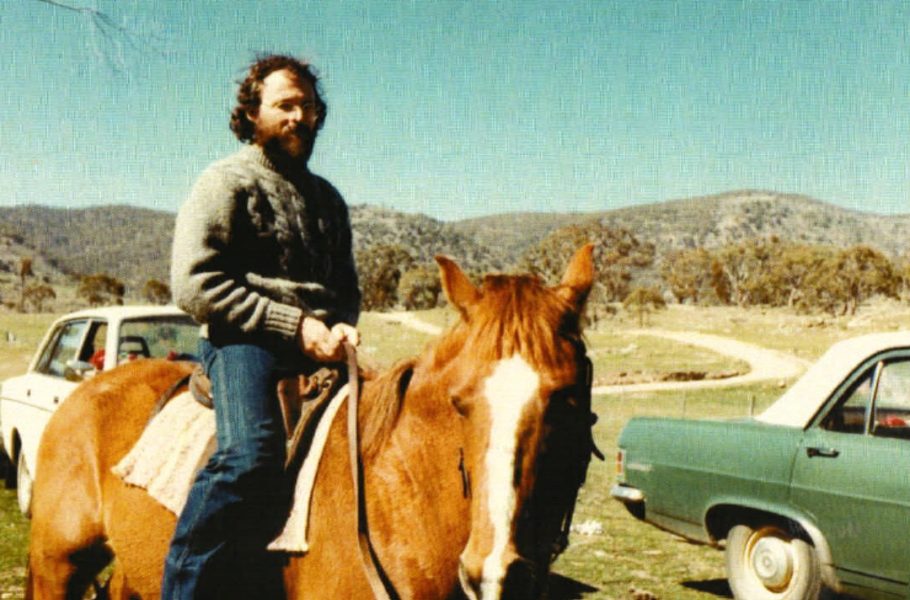

Easy rider: Greg Taylor enjoys some time out from actuarial pursuits on a farm in NSW, 1977

Going right back to your beginnings, how did you decide the actuarial profession was for you?

It’s a shameful story! I grew up in Adelaide and performed reasonably well at school but always regarded study as an unfortunate nuisance. I made a very poor decision in my final year of high school, abandoning science subjects to gain some soft options for myself – very silly – though I persevered with maths because it involved no effort. I was just looking for an easy life.

My family lived modestly and my parents had suggested engineering to help me rise out of the mire. We’d never heard of actuaries, hardly anyone in Adelaide had. But after a door-to-door insurance agent regaled my father with tales of these people who earned vast sums, I thought that sounded pretty good.

I figured the course would be fairly simple for me to knock off. Foolish! A decision without foundation or wisdom, and it meant no university. Instead, at age 16, I began actuarial study – a correspondence course in those days – and took a job at MLC Assurance Company in Adelaide.

How did your parents respond at the time to the path you chose?

My mother was always extremely proud. My father was a product of his era – enigmatic, a man of few words, so I was never entirely sure how he felt.

What kind of person was your father – what did he do?

His qualifications were never clear to me. That generation of people had very chequered careers because they came through the depression, then the war. He seemed to be a semi-qualified accountant. He then became a newsagent and later bought a clothing business, which he managed for many years. He was an entrepreneur, no doubt.

He went to war in New Guinea, but never talked about it. When I was eight or 10, war was glorious to me. I was born in the very last months of the war, in 1945, and I couldn’t get enough of it. But when I asked him about it, saying, ‘Why can’t we go to Anzac Day and march? Why don’t you go down to the pub with all the guys?” He just said to me, “The people who want to talk about it weren’t there.”

It affected him and many others very deeply. They were very brutalised.

It’s perhaps apt you’re known for treating people in a very human way. How did your ethical passion come together in business with your mathematical passion?

It consists of two components. The first is to do the right thing, and that involves being honest and telling people exactly what you think. The second is if you tell them what you think when it’s uncomfortable for them, then they know they can rely on you for an honest opinion.

It’s easy to say things a client wants to hear and it’s hard to say things they don’t want to hear – but the reward for that is trust. This was top of mind when we began Taylor Fry. You know the old saying, ‘what’s my opinion on this? What opinion would you like?’ We were very careful to avoid falling into a ‘yes men’ mould like that, and I always found honesty generally profitable.

Occasionally, it has the opposite effect, when a client can’t afford to hear honest advice, even if they respect it, simply because it blows their business plan apart. Consequently, my rule of thumb was I’d be fired roughly once every 10 years!

How did that affect you when it happened?

It’s not pleasant. It’s easy enough to say all this now but, at the time, there’s a great deal of self-doubt. You think, I’ve given my advice and I’ve stood by it, but am I being obstinate? Could I have done something else?

It’s one thing as a consultant to be fired by a client – it’s not great, but you can move on. It’s quite another thing as a corporate employee to be fired or, more likely, to be sidelined – constructive dismissal, it’s called. That’s a lot more serious from a personal viewpoint.

Not only is there self-doubt but paranoia can easily set in. What else will they do? Maybe they want to discredit me, damage my reputation. It’s extremely unpleasant, but there’s nothing you can do. As with any journey, you can only keep putting one foot in front of the other. Eventually, everything comes right or everything goes wrong. Fortunately, it hasn’t all gone wrong for me.

Partners in time: Greg Taylor at home in 1990 with wife Rhonda

One of your career highlights is setting up Taylor Fry. How much of an impact did it have on you?

I’m generally very bad at entrepreneurial activity, it’s not at all natural for me, so it had a considerable personal impact. I had to try to think as a leader, rather than a follower who sits in a corner working away quietly. I needed to change my perspective in everything I did, to consider how the company’s ability to gain and maintain business would be affected.

Luckily, there was a certain acceptance of the more bookish personality in the industry then. Some clients even seemed to regard it as an advantage.

When you look back at your time there, what place do Martin and Alan have in those reflections?

In Martin’s case, he was such an effective head in our Melbourne office, we always knew it wouldn’t require our mental energy. And he’s a good friend. It’s certainly a bonding experience jointly mortgaging your houses.

It’s a very different relationship with Alan – we go back a long way. Of course, I’m much older, although the gap’s narrowing now! He was a university graduate, about 21 or 22, when we first met, and I hired him for his first consulting job. This was at PwC (Coopers and Lybrand back then) and he was gung-ho from the start – a good thing because I’m not at all like that. Alan has always been a good counterbalance to my personality. It was bonding because we were a group of only five or six in those early C&L days.

There have been a few experiences with Alan. Once, when he was working in the US and still assisting me with research in Australia, we devised a ruse to create a research meeting in New Orleans. When we arrived, the city’s famous jazz festival was on, which we hadn’t anticipated. Consequently, our ‘meeting’ started at midday and ended at 6am.

What was the impetus to leave Taylor Fry after 15 years and was it difficult to return to academic life after many years running your own business?

It wasn’t difficult at all – I’ve always had one foot in each camp. I also grew up at a time when 65 was the conventional retirement age, so it was a landmark age for me. Once I decided, I looked forward, not back and as the date approached, I realised there were other things I’d like to be doing.

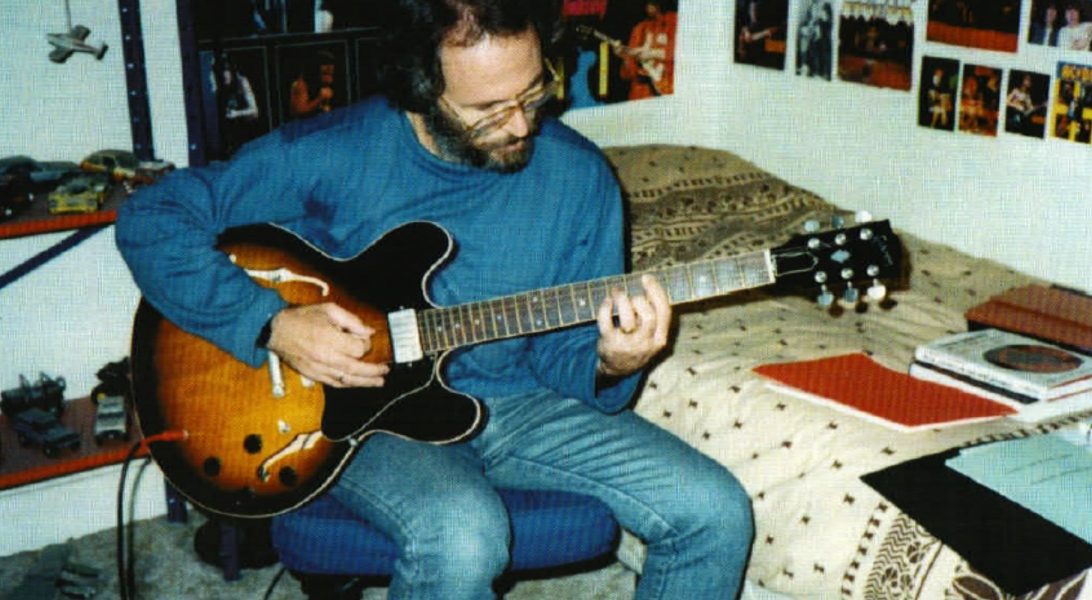

For example, I had musical interests before, playing guitar. As a child, I spent a great deal of time with a neighbourhood friend whose family was musical. It was very inspiring. I was about 10 when I resolved to play the guitar – despite my mother dismissing it as a ‘cowboy’ instrument.

After we established the company, I tried to continue, but the demands of a new organisation were all consuming, and half-measures were unsatisfying. It was a sacrifice to pack away the instrument, a wrenching experience. I had spent the previous 14 years working hard at being a guitarist developing jazz skills, so this was a big factor in considering new possibilities when I left Taylor Fry.

Nowadays, I still prefer jazz, and challenge myself with rock, blues and country. It’s a solitary pursuit, with the very occasional public exception. And no singing, just the music.

And all that jazz: Greg Taylor's passion for playing guitar began at age 10

On top of your musical accomplishments, you have also completed two PhDs – what compelled you?

The wrong decisions of my youth began to haunt me. I was shamed by my lack of qualifications in areas I enjoyed but abandoned. As an actuarial student, I didn’t even have an undergraduate degree, and I was terribly frustrated by the pragmatism and inelegance of actuarial theory. At that point, I wasn’t sure I wanted to be a practising actuary.

I’d had my eye on a brand-new actuarial course at Macquarie University and, in 1969, joined the faculty, teaching and researching.

During all of this, the Vietnam war had become a factor. Australia was involved in the war in a big way by then. It was a highly political subject – more horrible than we knew. I had been drafted for national service and deferred twice already because of my studies. The third time, in 1971, my application for exemption was denied.

When I was called to attend a medical examination, a football injury I’d recently sustained prevented me from enlisting. At first, the examining doctor didn’t believe I couldn’t straighten my arm, but he eventually accepted the truth and that was the end of that. I extended my research into an actuarial mathematics PhD over the next three years and it was more or less an armchair ride.

The science PhD came at an incredibly exciting period of discovery in theoretical physics – in fact, the last major advance in that field was in 1984. There were fundamental advancements in the Sixties and Seventies and I wanted to be part of it.

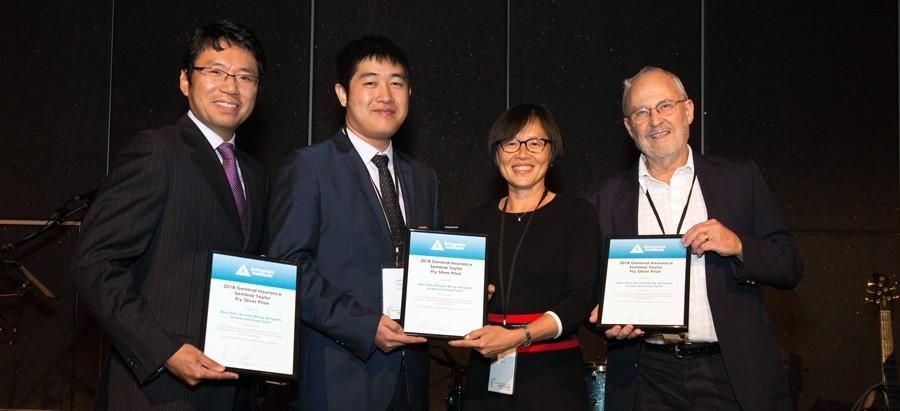

Greg Taylor receiving the Actuaries Institute Taylor Fry Silver Prize

With your passion for research, you could easily have remained exclusively in academia, yet you chose to traverse the academic and commercial worlds throughout your working life. Why?

An experience in the UK was pivotal. In 1975, my sabbatical year, overseas travel was very rare, but I was keen to explore and spent my time in England, Scotland and Switzerland. I had written a nice letter to the UK government actuaries department and was offered a job in a small unit at the department of trade, formulating new ways of assessing insurance companies following a large UK insurance failure in the Sixties.

The unit was headed by Bobby Beard*, a very, very famous actuary at the time. To work with him, well, you just couldn’t say no. He was the guru of the time.

I went along thinking he was like a god and I wouldn’t get to talk to him, but he always listened to me and was interested in my ideas. I couldn’t believe it. And he was a very nice guy. In my experience, the people at the very top of their professions have been the most approachable.

That year, and Bobby in particular, influenced me enormously in pursuing a consulting career. It confirmed my own thought that an actuarial fellowship would equip me to explore much more than academia.

*In 2008, Greg was awarded the Finlaison Medal by the UK’s Institute and Faculty of Actuaries, a nostalgic salute to his revered mentor Bobby Beard, who had also received the accolade, 36 years earlier in 1972, then known as the Silver Medal.

Over time, claims reserving became your specialty – what sparked your interest?

I fell into it at first. When general insurance began to acquire actuaries, they rarely did anything other than claims reserving, so that’s where I started.

Then, within the first six months of my consulting career, I became involved in legal proceedings that focused on loss reserving – and my interest was sharpened. The argument back and forth and objections raised about my methodology motivated me to innovate and improve it. When the legal proceedings ended after three years, I couldn’t pack it up and never think about it again.

What do you see as your most meaningful contribution to the actuarial profession?

I’ve never thought of it on any grand scale. It’s a collection of small things. I would like to think my endeavor to promote more analytical approaches to loss reserving has rubbed off in some way. You can shift people’s thinking marginally, and influence them to think that maybe we shouldn’t just look at a bunch of numbers and make an informed guess, that we should use more formal analysis sometimes. That’s the contribution I’d like to make.

What is the biggest lesson you’ve learned?

That pursuing the qualities of integrity and honesty doesn’t necessarily have great drawbacks. For me, there has been no real punishment. I was fired every 10 years, but that’s not much, you know.

In retrospect, it also seems significant that we aspired to create a culture at Taylor Fry where people are happy and feel valued. We just thought It was a good way to do things. It was more important to us than making huge amounts of money.

You seem to inspire so many people. Who or what inspires you?

I’m always inspired by the people whose thought processes I can see are reaching beyond mine – when I think, I wish I could have done or said that.

What are your hopes for your future – professionally and personally?

There’s always more to achieve! I’ll continue researching – I’m always looking for new things. It’s easy not to venture outside your area of authority, but to me that’s stagnation. Ultimately, you enter your dotage and lose relevance, but there’s more to be done in the meantime.

Music is a much more difficult area. I’m confronted daily with my inadequacies, but I don’t think I’m losing dexterity yet. There’s no shortage of challenges, so I’ll continue to enjoy it while I can. I do recognise there’ll come a time when it isn’t possible, but that can wait until the day it happens – I don’t look too far ahead. I remind myself every day how lucky I am.

Enjoy this read? Take a look at our piece on Taylor Fry co-founder Martin Fry

Want to know more about the history of Taylor Fry? Check out our About page

Recent articles

Recent articles

More articles

Taylor Fry boosts climate expertise

Climate and financial risk specialist Dr Ramona Meyricke rejoins our ranks to lead our climate practice, as we focus on meaningful solutions

Read Article

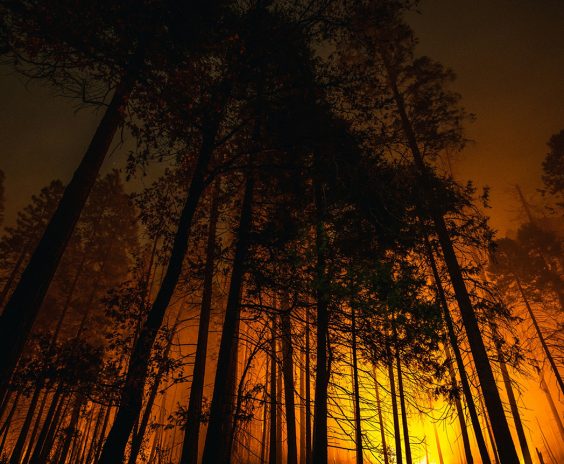

LA wildfires – implications for the upcoming Australian reinsurance renewals

What are the flow-on effects of the January LA wildfires in Australia?

Read Article